Part of a 20 km (12.5 miles) network of horse drawn tramways linking Ticknall with the Ashby Canal.

Ticknall, Derby

The Ticknall Tramway was part of a complex of tramways constructed to link the brickyards, lime quarries and lime yards of Ticknall to the Ashby de la Zouch Canal. Other sections linked to Cloud Hill quarries and lime works and Smoile and Lount collieries. A canal connection had originally been proposed, but this was abandoned because of water supply and cost problems.

The tramway of 20 km (12.5 miles) consisted of cast iron flanged rails, 0.91 m (3 ft) in length weighing an average of 17.3 kg (38 lbs) mounted on stone sleeper blocks of not less than 68.2 kg (150 lbs). This system of using a flanged rail and a flat section wheel was known as a plateway, as opposed to the flanged wheel and flat rail of a railway. The rails were cast at Outram's Butterley foundry and he estimated that they would absorb the full capacity of the works for 15 months. The gauge was 1.27 m (4 ft 2ins), an increase of 203 mm (8 ins) over Outram's earlier tramways because he believed that the additional width would give greater capacity for general freight. The tramway was double tracked south of Old Parks, but single tracked with passing places elsewhere.

Cuttings and embankments within the park and adjoining farmland can still be seen as well as an accommodation bridge still in use for farming. The main engineering features are the bridge over the A514 in Ticknall village, known as the Arch, and two tunnels within Calke Park, one of 122 m (402 ft) length under the main drive from the A514 to Calke Abbey. This Grade II Listed Structure avoided the tramway having to cross the driveway to the Harpur family residence of Calke Abbey, thus preserving the appearance of the park. This cut and cover tunnel, with an arch like a canal bridge, is one of the world's oldest railway arches and the National Trust is considering creating a walkway /cycleway along the line of the tramway. Sleeper blocks can be seen in various places along the route.

The Tramway was in use for a little over a century, last used in 1913 and formally closed in 1915. R B Schofield in his biography of Benjamin Outram describes the tramway system as being "well ahead of its time" and "a milestone in transport technology and a model for the modern railway systems which followed thirty years later."

The Ticknall Tramway

By Martin Allen (reproduced here with his kind permission - and with thanks to Barrow Hill Engine Shed Society)

Early land transportation in the British Isles developed as a means for the efficient conveyance of commodities and progressed in parallel with technical innovations in construction. Firstly, there was the Turnpike or Wagonway, which used pack horses or carts for short distances by roads. However, the horses had to be exchanged frequently for fresh ones over longer distances.

From the beginning of the 16th century, the earliest horsedrawn Tramways or plateways came into existence. The first one to be accurately recorded was at Wollaton Hall in Nottinghamshire, where Lord Middleton owned a colliery. Manuscripts surviving from 1597 refer to coal haulage as being “On our rails and bridges by ourselves, as the cartway is so fowl (sic) as few carriages can pass”. At this date however, the rails referred to would have been hardwood timber battens, as the first cast iron rails did not evolve until around 1767. This leap in innovation was at Coalbrookdale where the local iron foundry had its own internal Tramway, whose timber rails were being constantly worn out. Having the means to successfully produce cast iron rails on their own premises, they were found to be suitable and then offered commercially. The Nunnery Colliery in Sheffield also had similar Tramways, both underground and on the surface as from 1776. The site of this colliery is now occupied by the depot and headquarters of the Sheffield Supertram system, nicely maintaining the traditions of the earlier Tramways. By 1788, Joseph Butler had established an ironworks at Wingerworth, near Chesterfield and he was also offering cast iron Tramway plates.

The Ashby Canal was first advocated in 1792. The route would start from Moira Colliery, just south of Burton on Trent and then reach as far south as Nuneaton. Here, there would be a physical connection with the existing Coventry Canal. The Harpur family developed the mineral rights of the area around Ticknall and they acquired Calke Abbey together with the adjoining lands in 1760. The site has its origins as an Augustine priory in the 12th century and the present building dates from the 18th century. The Ashby Canal Company recognised the minerals potential of the area and had previously investigated a direct feeder canal to serve Ticknall. However, this was discounted owing to the high cost, mainly due to the flights of locks that would be required because of the terrain and the difficulty in obtaining the necessary water supplies. The legal provisions for building a Tramway were provided for within the Act of Parliament granted for the canal construction on 25th May 1794.

Benjamin Outram (1764-1805) had extensive experience as an engineer and a contractor of both canals and Tramways. He was engaged as an advisor by the managing committee of the Ashby Canal Company and the route was surveyed during January 1799. However, probably due to cash flow issues, it was not until 1st April 1799 that the project was approved by the committee. At this time, the estimated cost for the Tramway was stated to be £29,500 and the proposed completion date was given as 1st May 1801.

The iron rails used at Ticknall were only 3’-0” long (915mm) and weighed on average 38 pounds (17.3kg) each. They were pegged into roughly hewn square stone blocks weighing approximately 150 pounds (68.2kg) placed at each rail joint. The blocks had holes in the center for wooden dowels, through which iron spikes were driven to retain the rails. Unfortunately, cast iron is very brittle by its nature and breakages of the rails were frequent. Keeping the two rails to the correct gauge also proved to be problematic, as there were no sleepers or tie rods provided to maintain the rails at the correct gauge. Each stone block had a pocket dug into the ground with a bedding of shingle added to allow for adjustment. Reliance was placed on the weight of the stone blocks to hold the rails in stable alignment, providing that the shingle bedding was well packed. The rails were cast integrally with upstand flanges forming an “L” shaped cross section and the wagon wheels were flangeless with flat treads. This allowed the wagons to be taken by road as part of their journey, if necessary. In reality, when operating off the Tramway, the very narrow wheel treads on the wagons badly damaged the road surface and consequently this practice of transshipment was not ideal. The rail breakages mainly occurred where adjoining roads crossed over the tracks and wagons were manhandled on and off the tram road. To mitigate the breakages, bylaws instructed that “No loaded wagon driven off any of the said railways shall be suffered to return thereon over the flanches (sic) of the rails, without the same being first unladen”. In some of these locations where Tramway met highway, the original rails were replaced by ones having two strengthening ribs cast on the underside for added reinforcement, but breakages still persisted.

It was demanded by the landowner, Sir Henry Harpur that the Tramway should not spoil the view from Calke Abbey and must therefore pass under the main driveway of the abbey in a tunnel. Construction of the tunnel under the road was by the “cut and cover” method, in which a broad trench would firstly be dug out. The tunnel lining itself would then be built in brick and once sufficiently hardened was covered over again, using some of the soil which had been set aside from the earlier excavation. This allowed the view of the landscape to revert to its former state and thus the land owner was appeased. The added advantage is that this method of construction would be cheaper (and probably quicker) than building a deep V-shaped open cutting with sloping earthwork on each side. The finished tunnel at Calke Abbey was 138 yards (126m) long. Four metal grilles were provided in the crown of the tunnel for natural light and ventilation. The grilles are still visible today in the grass above. The route also included a brick arched bridge of typical canal engineering style, taking the Tramway over the public highway at Main Road (now the A514) in Ticknall. Now, this bridge is a Grade 2 Listed structure and is considered to be one of the oldest surviving railway arches in the world. There were two other tunnels on the line, a short one named Basfords Hill which lies to the south of Ticknall and is 51 yards (47m) long. At Ashby Old Parks is the longest tunnel, at 447 yards (409m). In 1951, Charles E. Lee the noted railway historian, accurately measured the inside bore of the Calke Abbey tunnel. He found it to vary in places from 7’-1” (2.2m) to 12’-1” (3.7m) wide and 6’-9” (2.05m) to 7’-8” (2.3m) high.

An order was placed in April 1799 with the Butterley Ironworks to supply the first batch of cast iron rails, sufficient for five miles of track and having a total weight of 700 tons, with delivery to be during the following July. The tramway committee had prevaricated over a start date for the construction, due primarily to a lack of funds, but finally instructed that the construction should proceed as from 6th August 1799. The committee however, neglected to sign any contractual agreement with Outram and this serious omission was soon to cause significant delays in the completion of the works. By 13th September, it was however agreed that Outram should firstly commence work along the Ticknall branch, as earthworks including deep cuttings at Old Parks and the tunnel under the Calke Abbey driveway would both be time consuming projects. Notwithstanding this enthusiasm to proceed, Outram was still insisting on 3rd December that his contract be signed and there were frequent complaints about the delays in receiving regular payments for work done. Finally, the Tramway was operational by 1802, subject to some repairs and adjustments. Outram was eventually paid a total of £31,164 by March 1805, which was in excess of the original budget but included some additional works that were instructed by the management committee. Regrettably, Outram had little time left for him to enjoy his success, as he died aged 41, on 22nd May 1805. His widow was later to receive the final payment of £450 long overdue to him.

The Tramway was worked by teams of horses and the chosen track gauge was unusually set at 4’-2” (1270mm). Tramways previously built by Outram had all been to 3’-6” (1066mm) gauge, but it was reasoned that the increased width allowed for more efficient payloads. The Butterley Iron Company built the wagons or “tubs” to their own standard design, having a wooden body with an end door hinged at the top, for discharging the load by tipping. The Tramway reached the Ashby Canal at Willesley Basin near Blackfordby in neighbouring Leicestershire, where the cargoes were transshipped into canal boats. Two horses were required to haul each rake of wagons on the level sections in the south west. This was supplemented by a third horse on the steep uphill section in the north east, where the load was limited to two wagons. This horse was then led back down the hill by a boy, in order to be ready for the uphill run of the following wagons. In busy times, the average working pattern was two trains in the morning and another two in the afternoon. Altogether, four men and one boy were required for each shift, controlling nine horses between them. Typically, a rake of loaded wagons totaled forty tons when loaded with limestone on a downhill run. Some of the hand brakes on the wagons would have to be pinned down on the descents to prevent runaways. On the return journeys, twelve tons of coal or other commodities could be hauled uphill.

The route of the tramway was of a “Y” shaped configuration, with the main trunk having double track and the two principal branches were single track. The convergence point was at Ashby Old Parks, near to the village of Smisby. The two branches were north of Ashby and each served lime pits, to the west at Calke Abbey and to the east at Cloud Hill, near the village of Breedon. No doubt the single track branches were built as such to effect economies, but it was later found necessary to insert no less than 12 passing loops in both branches. The total length of the running lines amounted to 12 miles 43 chains 13 yards (20.65km). A detailed map has survived which shows the locations of the problematic road crossings, of which there were at least 15 and this was where the majority of the rail breakages occurred.

Commercial business on the combined canal and Tramway appears to have improved considerably in the period from about 1823 to at least 1830. Surviving books of accounts however do not differentiate between receipts from the respective undertakings. Overall profits were therefore reflected in the number of improvements then being funded on the Tramway. Firstly, a public loading wharf was provided at Ticknall in 1823 for general merchandise. A three mile Tramway from the canal at Moria northwards towards Swadlincote was opened on 21st July 1827 at a cost of £4,262 to serve collieries and potteries in the district. This line was isolated from the main Tramway and employed a different type of cast iron rail. In 1829, two additional lines off the Ticknall branch were built to serve another lime pit at Dimminsdale. In the following year, a lime works at Staunton Harold was also provided with a Tramway connection.

The Midland Railway under its Chairman George Hudson, obtained an Act of Parliament on 16th July 1846 in order to acquire the interests of the Ashby Canal Co. and with it, the Tramway for £110,000. The Midland intended to lift part of the Tramway and in the process, convert it to a conventional standard gauge railway. This required the original tunnel at Ashby Old Parks to be opened out to suit the increased loading gauge and the length at the south end was reduced by 139 yards (128m). This tunnel was always troublesome, owing to it being built under a pond which constantly leaked into the tunnel. A further extension of the standard gauge beyond Cloud Hill continued eastward, to ultimately reach the towns of Worthington and Melbourne. The route of the Tramway from Ticknall was thus cut back at Old Parks Junction. Here, a transshipment wharf was provided near the northern approach to Ashby Old Parks tunnel, to exchange commodities between the two undertakings. On 5th July 1865, another Parliamentary Act was obtained to extend the Midland line westwards, beyond the tunnel towards the town of Ashby De-la-Zouch. This enabled a new junction to be provided to connect with the existing Burton to Leicester railway and this was opened on 1st January 1874. Part of the Midland line became a section of the Melbourne Military Railway during World War Two. From 19th November 1939 to 31st December 1944, it was requisitioned from the LMS for use of the Royal Engineers as a training school. This included experimental railway bridge building and teaching railway operating personnel.

.

The Tramway became largely disused by 1913 and the last revenue-earning journey was on 20th May in that year. However, a single wagon was run empty in a return trip once every six months in order to keep the route viable. Ultimately, it was finally abandoned in September 1915 when the local industries fell into disuse, partly because the quarries were becoming worked out and the constraints of the First World War had curtailed much of the local trade. Additionally, the prevailing necessities of war and the need for scrap metal demanded the removal of the redundant rails for melting down. Despite the technology having been overtaken by more efficient methods of design and operation elsewhere in the country, the Tramway never the less continued to operate as originally intended for at least 110 years.

Today, Calke Abbey is a National Trust property. The tunnel near the Abbey was restored by the Trust in 1995 and the public can now walk through it. Much of the original route of the line can be readily identified today, especially as some of the original stone setts still survive in situ. Most of the route was converted into a public cycle way in 2014. Fortunately, a significant length of the original earthwork embankment also survives intact between Bryan’s Coppice and South Wood. Two of the limestone pits and an adjoining lime kiln can still be discerned, although overgrown in places and have now become a wildlife reserve with the status of a “Site of Special Scientific Interest”. The Transport Trust has designated the line as a Transport Heritage Site. In acknowledgement of the history of the line, one of the Trust’s “red wheels” commemorative plaques is mounted on the abutment of the Tramway bridge over the A514 road. In addition, several stone blocks from the trackbed are preserved in Leicester at the Newarke Houses Museum.

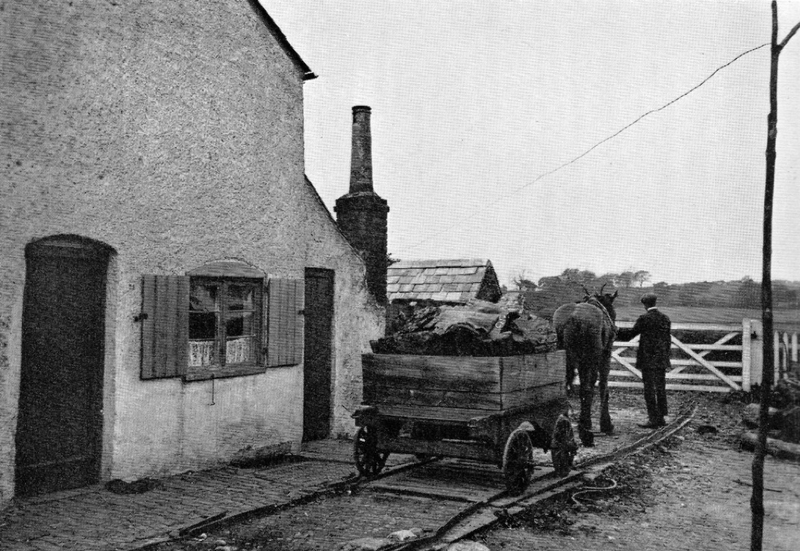

The Ticknall Tramway, with a wagon passing through a weighbridge, circa 1913. The photograph was taken during the period when the line was not in revenue service. However, it was operated once every six months in order to retain it as a right of way.

By road: On A514 is 16km (10 miles) south of Derby and 6.5 km (4 miles) south of the A50. Ticknall Arch, one of the tramway bridges, crosses the A514 in the centre of the village. Other parts of the tramway can be traced within and to the west of Calke Abbey Park - access from A514 and B5006 in Ticknall village. South of Old Parks, the tramway was replaced by a standard gauge railway in 1874 and is less traceable.

Calderbank, Gerry, Canal, Coal & Tramway: An Introduction to the Industrial Heritage of Mamble, L C Promotions, ASIN: B0019ZH4XQ (2000)

Holt, Geoffrey, The Ticknall Tramway, Ticknall Preservation and Historical Society, ASIN: B001TJP3XU (2002)

Schofield, R.B., Benjamin Outram 1764-1805 - An Engineering Biography, Merton Priory Press, ISBN-10: 1898937427 (2000)

Stabb, I. & Downing, T., The Redlake Tramway and the China Clay Industry, T. Downing, ASIN: B001OJUK6A (1977)

Webb, John Stanley, Black Country Tramways: Company-worked Tramways and Light Railways of the West Midlands Industrial Area: 1913-39, J S Webb, ISBN-10: 0950376418 (1976)

Association for Industrial Archeology

National Tramway Museum - Crich Tramway Village

Ticknall Preservation & Historical Society

Tramway & Light Railway Society

Waterways: People - Benjamin Outram